Specifically, he says that children’s novels “all balance the same set of opposites: home and exile, escape and security, the familiar and the foreign, the strange and the comfortable, fear and acceptance, isolation and togetherness, the disorderly and the patterned” and that “all in some way combine what one wishes for with what one must accept…and all create balances between these extremes” (Nodelman 1985, 18, 20). Indeed what one uncovers when one interprets high quality, beloved children’s books is not their thematic distinctiveness or originality, but their correspondences and similarities. Unfortunately, he finds that this is not the case with children’s literature. He asserts that interpretation should allow literary critics to figure out what makes good books better than not-so-good books, that it should bring to light those qualities that make a book unique or especially deserving of our esteem. In his essay, “Interpretation and the apparent sameness of children’s novels”, Perry Nodelman comes to a conclusion that seems to distress him. I’ll always come out on top”, (Lindgren 1997, 3) she informs us. Able to lift her horse and toss any number of men into the air without effort, she can also walk tightropes or plank bridges suspended in space, run on top of roofs and leap onto trees, ride bareback standing up, climb a tree with a filled coffeepot in her hand, shoot a rifle with unerring accuracy, eat poisonous mushrooms without effect, and steer a ship through storms. But these outward idiosyncrasies are nothing in comparison with her power and her strength. Lindgren always begins by describing her strange looks – carrot-red hair in braids that stick out, a nose like a potato, patches on her clothes and unmatched stockings – and her house and its inhabitants – a run-down dwelling in an overgrown garden with a monkey in a straw hat and a horse as roommates. Although, unlike Karlsson on the Roof she doesn’t have a propeller on her back, Pippi is extraordinary in other ways. The reader certainly has no quarrel with this observation. “Pippi was no ordinary girl”, (Lindgren 1997, 69) Astrid Lindgren tells us in one of her characteristic ironic understatements.

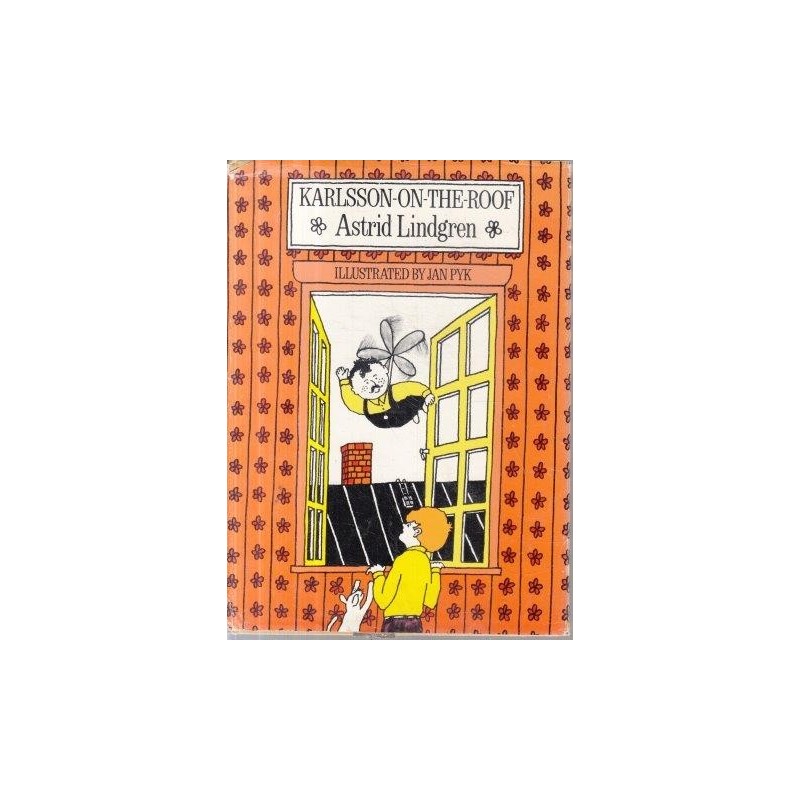

It is claimed that the domain of “whatifness”, by presenting alternatives to the ordinary, brings the reader closer to a better understanding of the conditions of their own Lebensform. First, it acquaints children with possible forms of “being other.” Second, it opens a sphere of “whatifness”, that is, the account of what the world would look like if certain concepts, or practices, were different. Presenting such otherness to the reader implicitly serves two pedagogical goals. While the existing language games’ rules constitute the sphere of the ordinary, the deviation from them forms the sphere of unusualness, extra-ordinariness, otherness, or “jiggery-pokery,” to use Karlson’s words. The otherness can be here understood as a distancing act from everyday language games, and the habits and Lebensformen that they function in. In such a reading, Karlson appears as a figure of the other. Instead, it is shown that the figure of Karlson may be better understood in the context of the later Wittgenstein’s conception of language games. Next, an attempt is made unsuccessfully to locate the figure of Karlson of the Karlson trilogy (Karlson on the Roof, Karlson Flies Again and The World’s Best Karlson) in this critical context. Inspired by Gaare and Sjaastad’s reading of Pippi Longstocking, the article discusses the philosophical ideas embedded in Lindgren’s books about Pippi Longstocking, stressing, in particular, Lindgren’s implicit critique of Western culture.

The article is mainly concerned with philosophical interpretations of Astrid Lindgren’s Karlson books.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)